Typescript Advanced Types custom or predefined

We will discuss the Record*, Partial, Required, *Pick and a custom Omit types.

- Record

- Partial

- Required

TypeScript has many advanced type capabilities which make writing dynamically typed code easy. It also facilitates the adoption of existing JavaScript code since it lets us keep the dynamic capabilities of JavaScript while using the type-checking capabilities of TypeScript. There are multiple kinds of advanced types in TypeScript, like intersection types, union types, type guards, nullable types, and type aliases, and more. In this article, we’ll look at type guards.

Type Guards

To check if an object is of a certain type, we can make our own type guards to check for members that we expect to be present and the data type of the values. To do this, we can use some TypeScript-specific operators and also JavaScript operators.

One way to check for types is to explicitly cast an object with a type with the as operator. This is needed for accessing a property that’s not specified in all the types that form a union type. For example, if we have the following code:

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

interface Employee {

employeeCode: string;

}

let person: Person | Employee = {

name: 'Jane',

age: 20,

employeeCode: '123'

};

console.log(person.name);Then the TypeScript compiler won’t let us access the name property of the person object since it’s only available in the Person type but not in the Employee type. Therefore, we’ll get the following error:

Property 'name' does not exist on type 'Person | Employee'.

Property 'name' does not exist on type 'Employee'.(2339)In this case, we have to use the type assertion operator available in TypeScript to cast the type to the Person object so that we can access the name property, which we know exists in the person object.

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

interface Employee {

employeeCode: string;

}

let person: Person | Employee = {

name: 'Jane',

age: 20,

employeeCode: '123'

};

console.log((person as Person).name);Type Predicates

To check for the structure of the object, we can use a type predicate. A type predicate is a piece code where we check if the given property name has a value associated with it. For example, we can write a new function isPerson to check if an object has the properties in the Person type:

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

interface Employee {

employeeCode: string;

}

let person: Person | Employee = {

name: 'Jane',

age: 20,

employeeCode: '123'

};

const isPerson = (person: Person | Employee): person is Person => {

return (person as Person).name !== undefined;

}

if (isPerson(person)) {

console.log(person.name);

}

else {

console.log(person.employeeCode);

}In the code above, the isPerson returns a person is Person type, which is our type predicate.

If we use that function as we do in the code above, then the TypeScript compiler will automatically narrow down the type if a union type is composed of two types.

In the if (isPerson(person)){ ... } block, we can access any member of the Person interface.

Then the TypeScript compiler will refuse to compile the code and we’ll get the following error messages:

Property 'employeeCode' does not exist on type 'Animal | Employee'.

Property 'employeeCode' does not exist on type 'Animal'.(2339)This is because it doesn’t know the type of what’s inside the else clause since it can be either Animal or Employee. To solve this, we can add another if block to check for the Employee type as we do in the following code:

interface Animal {

kind: string;

}

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

interface Employee {

employeeCode: string;

}

let person: Person | Employee | Animal = {

name: 'Jane',

age: 20,

employeeCode: '123'

};

const isPerson = (person: Person | Employee | Animal): person is Person => {

return (person as Person).name !== undefined;

}

const isEmployee = (person: Person | Employee | Animal): person is Employee => {

return (person as Employee).employeeCode !== undefined;

}

if (isPerson(person)) {

console.log(person.name);

}

else if (isEmployee(person)) {

console.log(person.employeeCode);

}

else {

console.log(person.kind);

}In operator can be used to do quick check if we have that property in object or not

interface Animal {

kind: string;

}

interface Person {

name: string;

age: number;

}

interface Employee {

employeeCode: string;

}

let person: Person | Employee | Animal = {

name: 'Jane',

age: 20,

employeeCode: '123'

};

const getIdentifier = (person: Person | Employee | Animal) => {

if ('name' in person) {

return person.name;

}

else if ('employeeCode' in person) {

return person.employeeCode

}

return person.kind;

}Typeof Type Guard

For determining the type of objects that have union types composed of primitive types, we can use the typeof operator. For example, if we have a variable that has the union type number | string | boolean, then we can write the following code to determine whether it’s a number, a string, or a boolean. For example, if we write:

const isNumber = (x: any): x is number =>{

return typeof x === "number";

}

const isString = (x: any): x is string => {

return typeof x === "string";

}

const doSomething = (x: number | string | boolean) => {

if (isNumber(x)) {

console.log(x.toFixed(0));

}

else if (isString(x)) {

console.log(x.length);

}

else {

console.log(x);

}

}

doSomething(1);Instanceof Type Guard

The instanceof type guard can be used to determine the type of instance type. It’s useful for determining which child type an object belongs to, given the child type that the parent type derives from. For example, we can use the instanceof type guard like in the following code:

interface Animal {

kind: string;

}

class Dog implements Animal{

breed: string;

kind: string;

constructor(kind: string, breed: string) {

this.kind = kind;

this.breed = breed;

}

}

class Cat implements Animal{

age: number;

kind: string;

constructor(kind: string, age: number) {

this.kind = kind;

this.age = age;

}

}

const getRandomAnimal = () =>{

return Math.random() < 0.5 ?

new Cat('cat', 2) :

new Dog('dog', 'Laborador');

}

let animal = getRandomAnimal();

if (animal instanceof Cat) {

console.log(animal.age);

}

if (animal instanceof Dog) {

console.log(animal.breed);

}In the code above, we have a getRandomAnimal function that returns either a Cat or a Dog object, so the return type of it is Cat | Dog. Cat and Dog both implement the Animal interface.

The instanceof type guard determines the type of the object by its constructor, since the Cat and Dog constructors have different signatures, it can determine the type by comparing the constructor signatures.

If both classes have the same signature, the instanceof type guard will also help determine the right type. Inside the if (animal instanceof Cat) { ... } block, we can access the age member of the Cat instance.

Record

A very useful built-in type introduced by Typescript 2.1 is Record: it allows you to created a typed map and is great for creating composite interfaces. To type a variable as Record, you have to pass a string as a key and some type for its corresponding value. The simplest case is when you have a string as a value:

const SERVICES: Record<string, string> = {

doorToDoor: "delivery at door",

airDelivery: "flying in",

specialDelivery: "special delivery",

inStore: "in-store pickup",

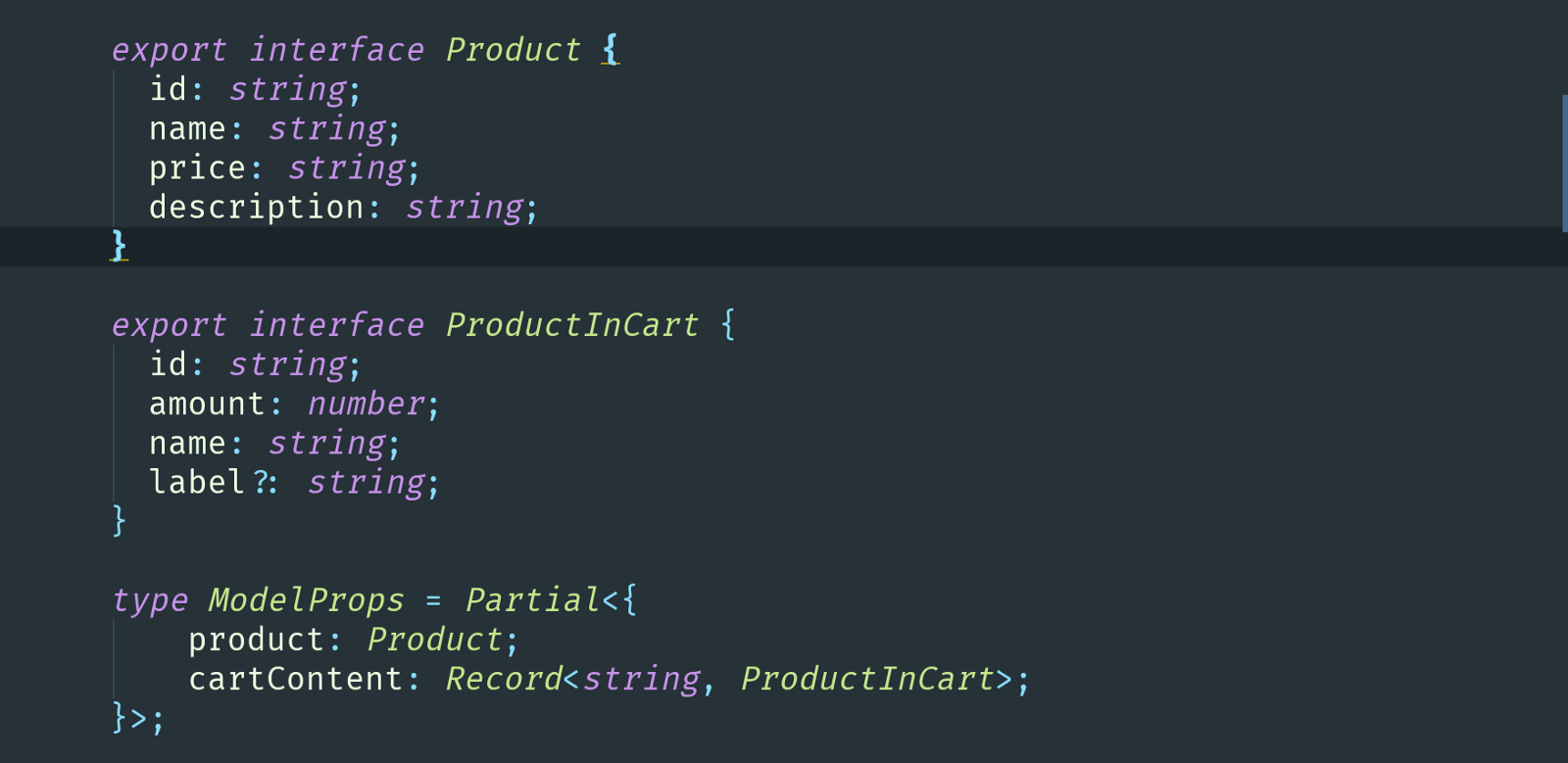

};This may appear trivial, but it provides easy typing in your everyday code. One of the popular cases when Record works in well is an interface for a business entity that you keep in a dictionary as key-value pairs. This model could represent a collection of contacts, events, user data, transportation requests, cinema tickets, and more. In the following example, we create a model for products that a user could add to her cart:

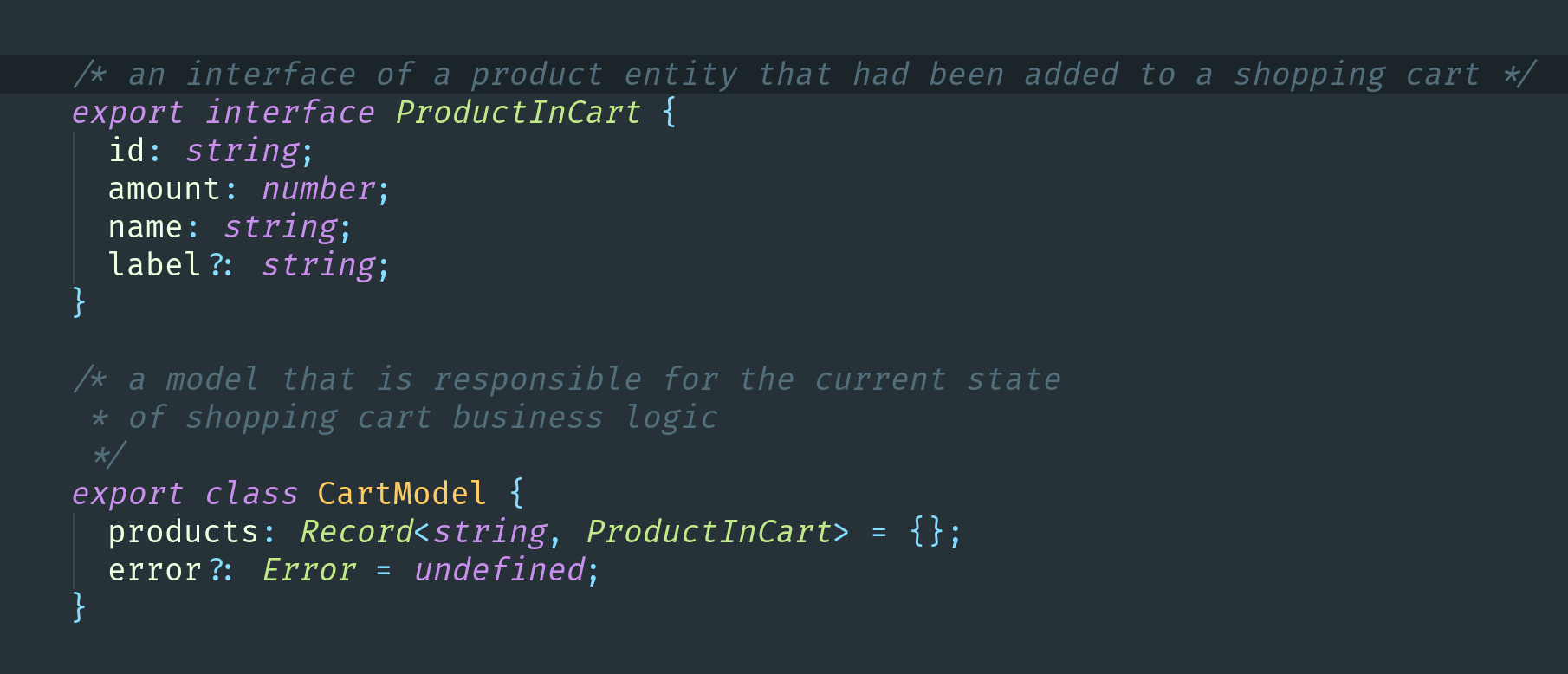

Type Record is used for a dictionary of products in a user cart.

Type Record is used for a dictionary of products in a user cart.

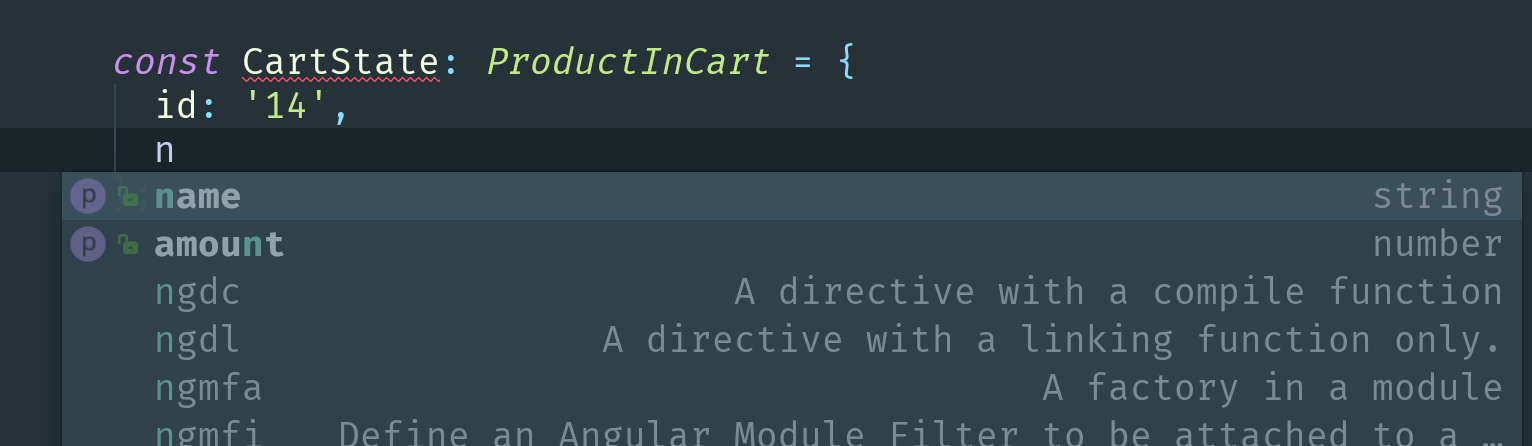

You see how the editor autocompletion will help us to define a typed object and will mark the variable with an error because not all the required properties are defined:

Webstorm autocomplete tool suggests to add name and amount for CartState variable

Webstorm autocomplete tool suggests to add name and amount for CartState variable

Also, Typescript does not allow us to create an empty object for some defined shape and then populate it with properties, but here Record will come to the rescue.

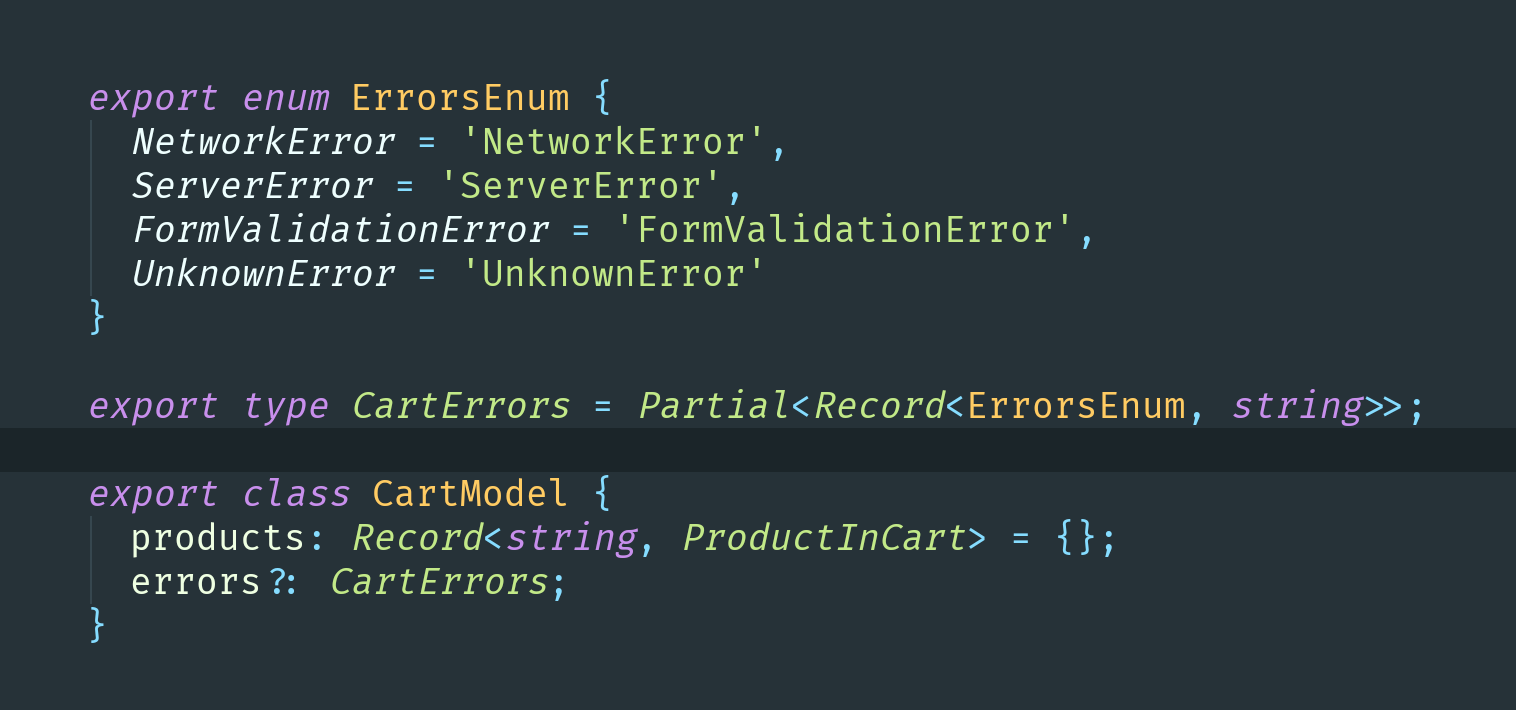

It is also possible to use a string enum as a key in the Record type. For example, we will use ErrorsEnum to keep and access possible error values (messages):

Use Record for errors dictionary in business model

Use Record for errors dictionary in business model

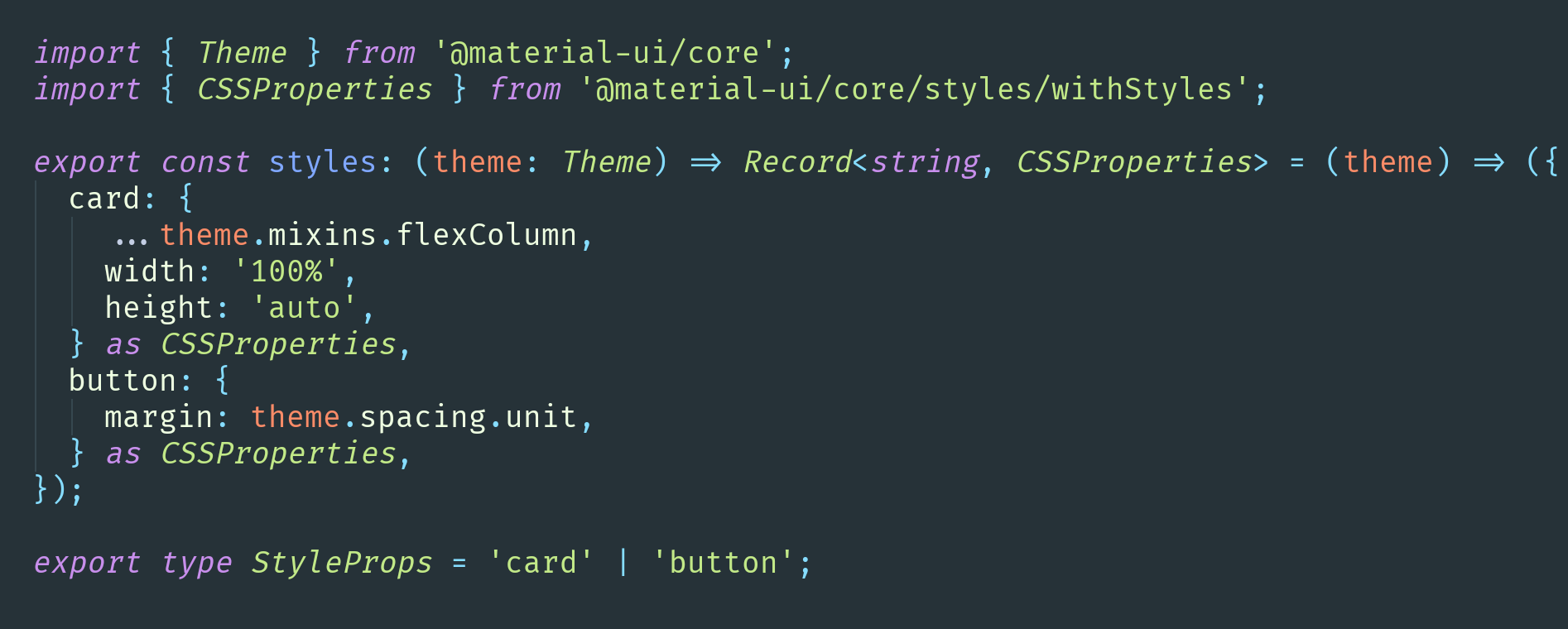

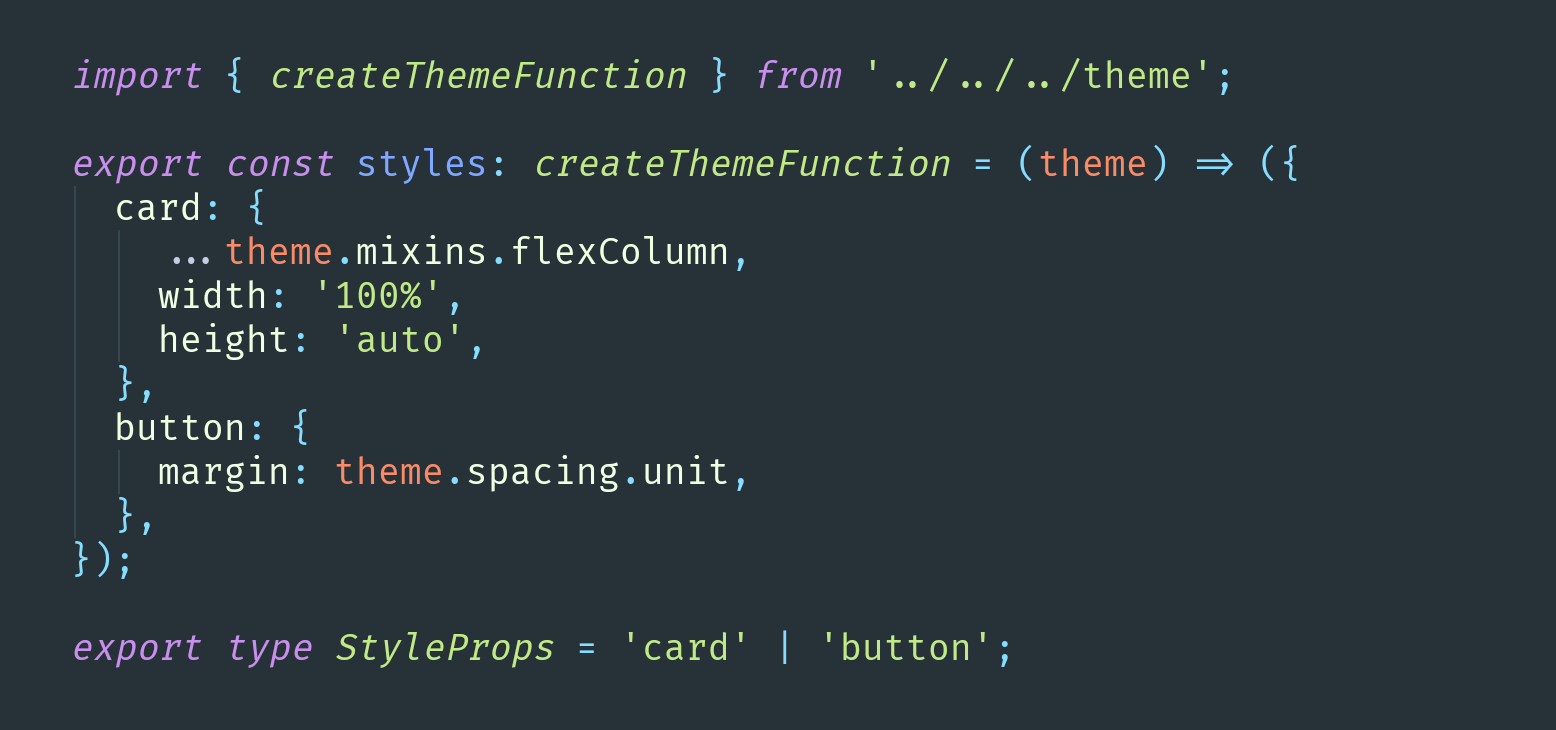

Let’s see how you can use it for type enhancing when working with Material-UI library. As the guide says, you can add your custom styles with CSS-in-JS notation and inject them via withStyles HOC. You can define styles as a function that takes a theme as an argument and returns the future className with correspondent styles and you want to define a type for this function:

Adding type for styles function in every component file

Adding type for styles function in every component file

You notice that it can become very annoying to add these as CSSProperties for every style object. Alternatively, you can use the benefit of the Record type and define a type for the styles function:

Using once defined createThemeFunction type everywhere

Using once defined createThemeFunction type everywhere

Now you can use it safely in every component and get rid of hardcoding type of CSS properties in your styles.

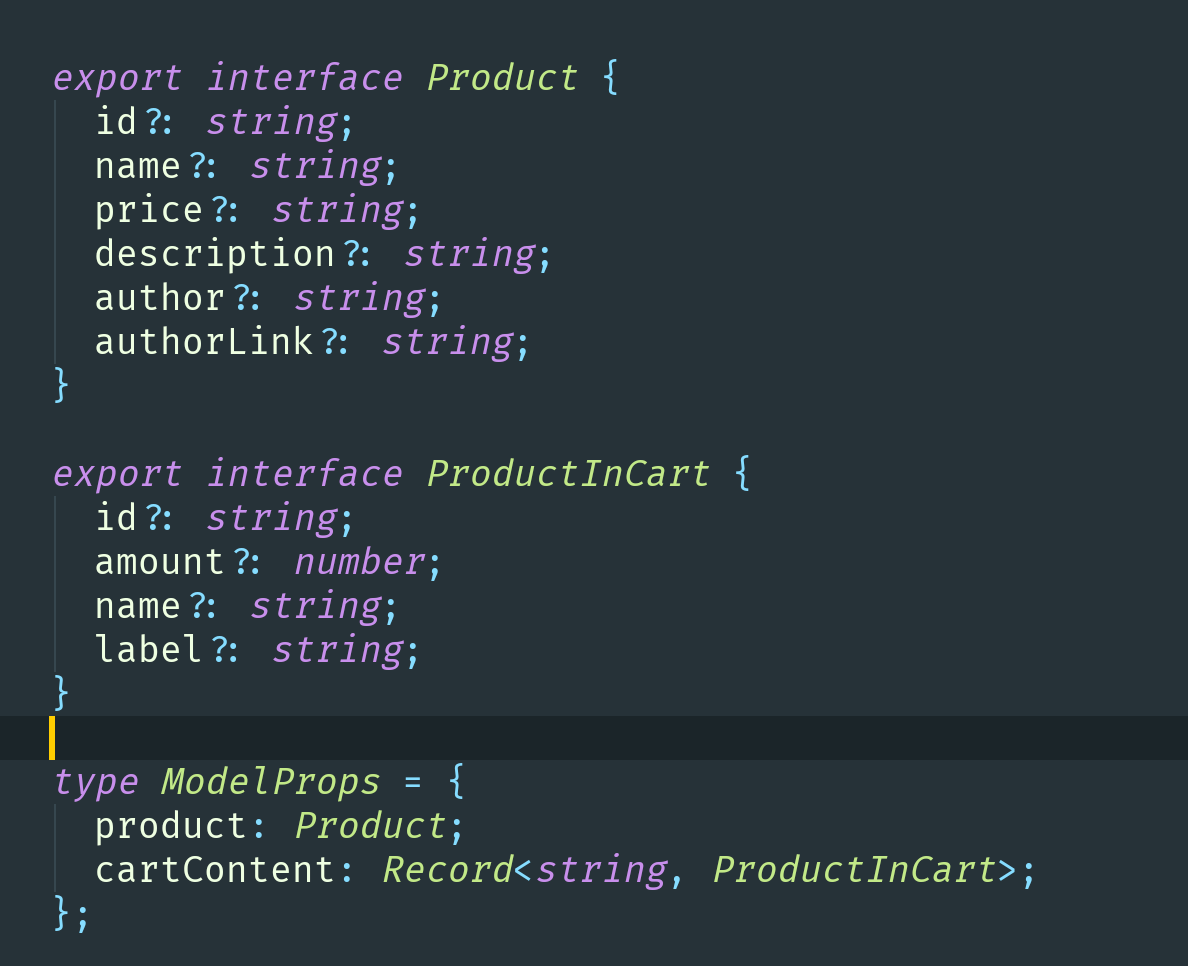

Partial and Required

Partial type makes all properties in the object optional. It could help you in many cases, like when you’re working with the data that a component would render but you know that the data may not be fetched at the moment of mounting:

On the left: using Partial type to reach the same result as on the right where every property is marked optional

On the left: using Partial type to reach the same result as on the right where every property is marked optional

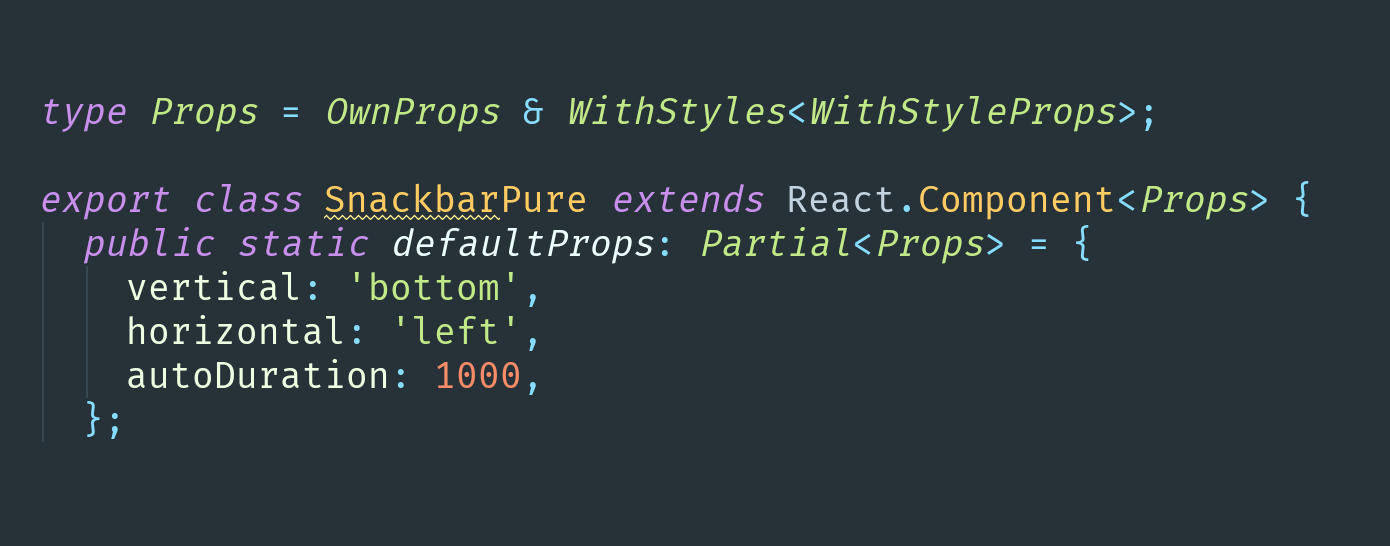

Or you can use Partial* *to define some of the props as default props for your component:

Use Partials in typings for default props

Use Partials in typings for default props

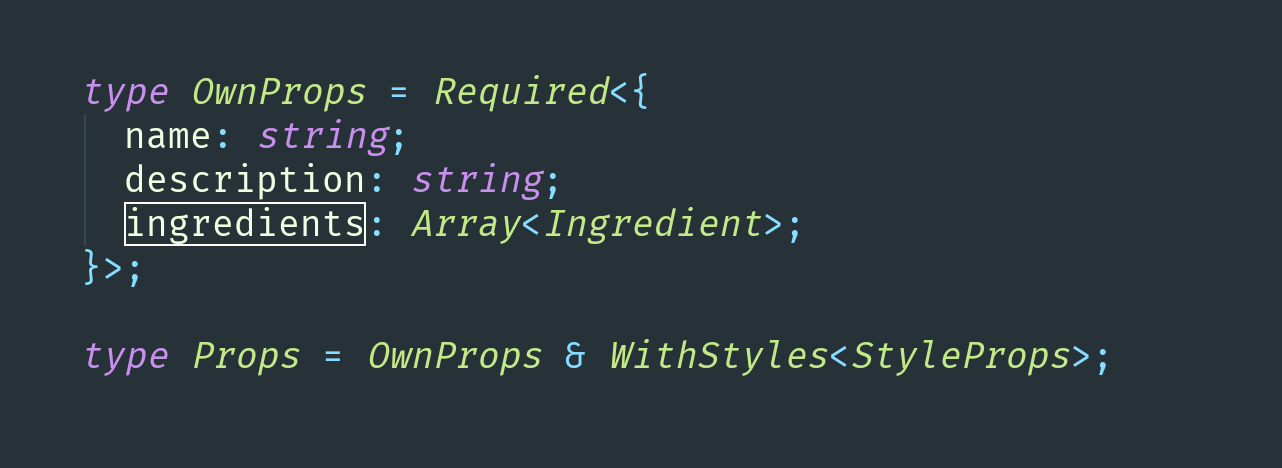

As the opposite, the Required built-in type introduced in Typescript v2.8, makes all properties of a described object required:

All fields in OwnProps of this component are required

All fields in OwnProps of this component are required

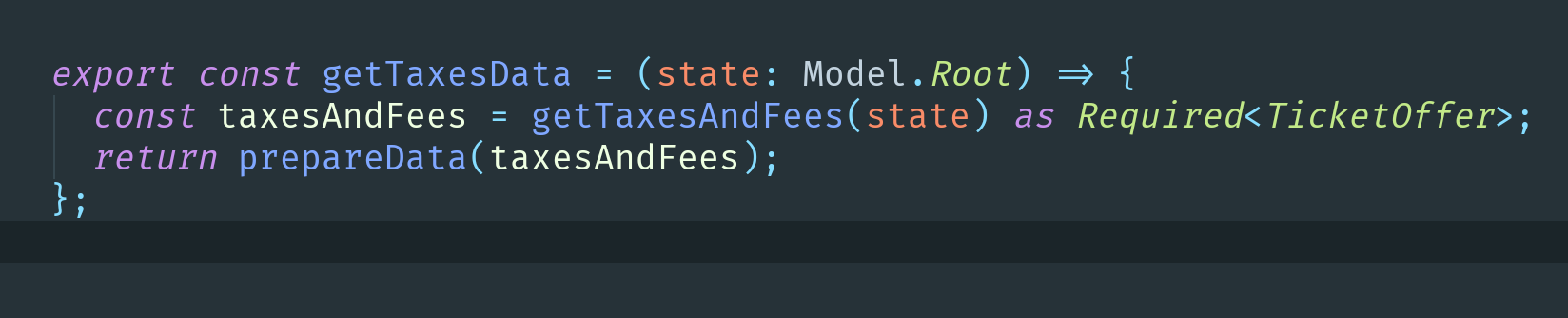

One of the use cases for Required is selectors: sometimes you want to make a selector for a property from a nested object and you know that at the moment of selector invocation this property will be defined. You may point it out with a typing:

A small hack to ensure compiler that ticketOffer is required for the selector processing

A small hack to ensure compiler that ticketOffer is required for the selector processing

This may look like a cheat and it can cause type errors if you start to inherit required properties from optional ones, so be careful!

Maybe it sounds stupid but it’s not a rare situation when you have code generated automatically and all interfaces that are in your hands are Partial and all elements of your UI want only Required. Here you’ll start to check every nested object on undefined 😨.

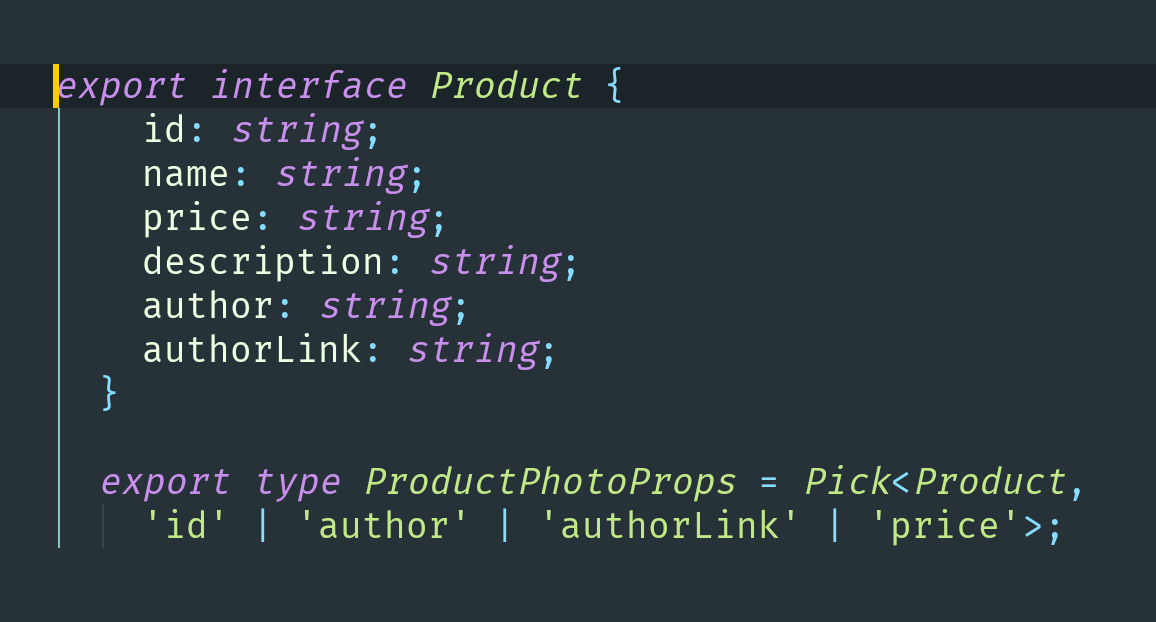

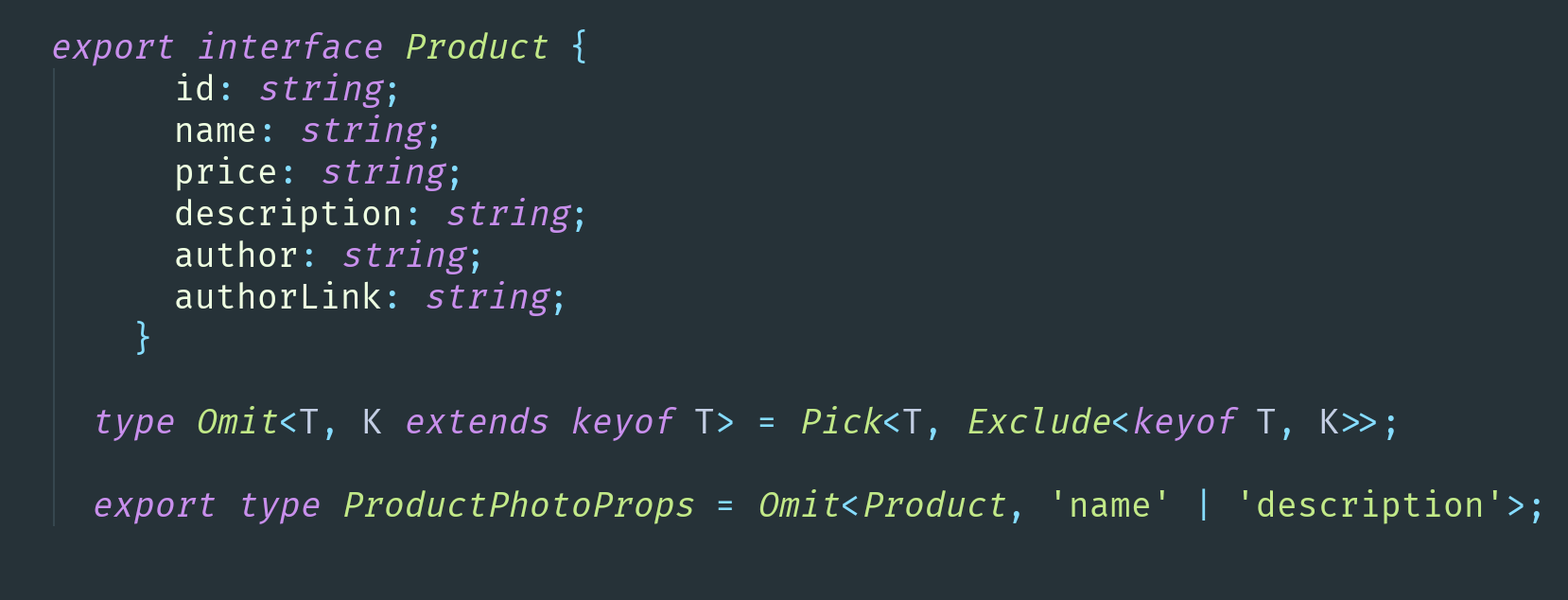

Pick and Omit

Have you ever tried to narrow a type because you realized that your next class doesn’t need this bunch of properties? Or maybe you arrived at this point in the process of refactoring, trying to distribute pieces of a system in a new way. There are several types that can solve this problem.

Pick helps you to use a defined already interface but take from the object only those keys that you need.

Omit which isn’t predefined in the Typescript lib.d.ts but is easy to define with the Pick and Exclude. It excludes the properties that you don’t want to take from an interface.

At both of these images, ProductPhotoProps will contain all Product properties except of name and description:

Pick and Omit are flexible ways to re-use your interfaces

Pick and Omit are flexible ways to re-use your interfaces

One of a practical example of such a situation from my current project is a refactoring a large form with a complex fields dependencies. There was FormProps type where errors field was included. After re-thinking this architecture the errors became unnecessary for a first child component but still needed by the second one. I used Pick to take a portion of fields except for errors for a new interface and it worked well.

There are, of course, different ways to combine types and define their relationship. If you start to decompose a large thing into small pieces from the beginning, maybe you will solve the problem of excluding properties from an object from another side. You would instead extend types.

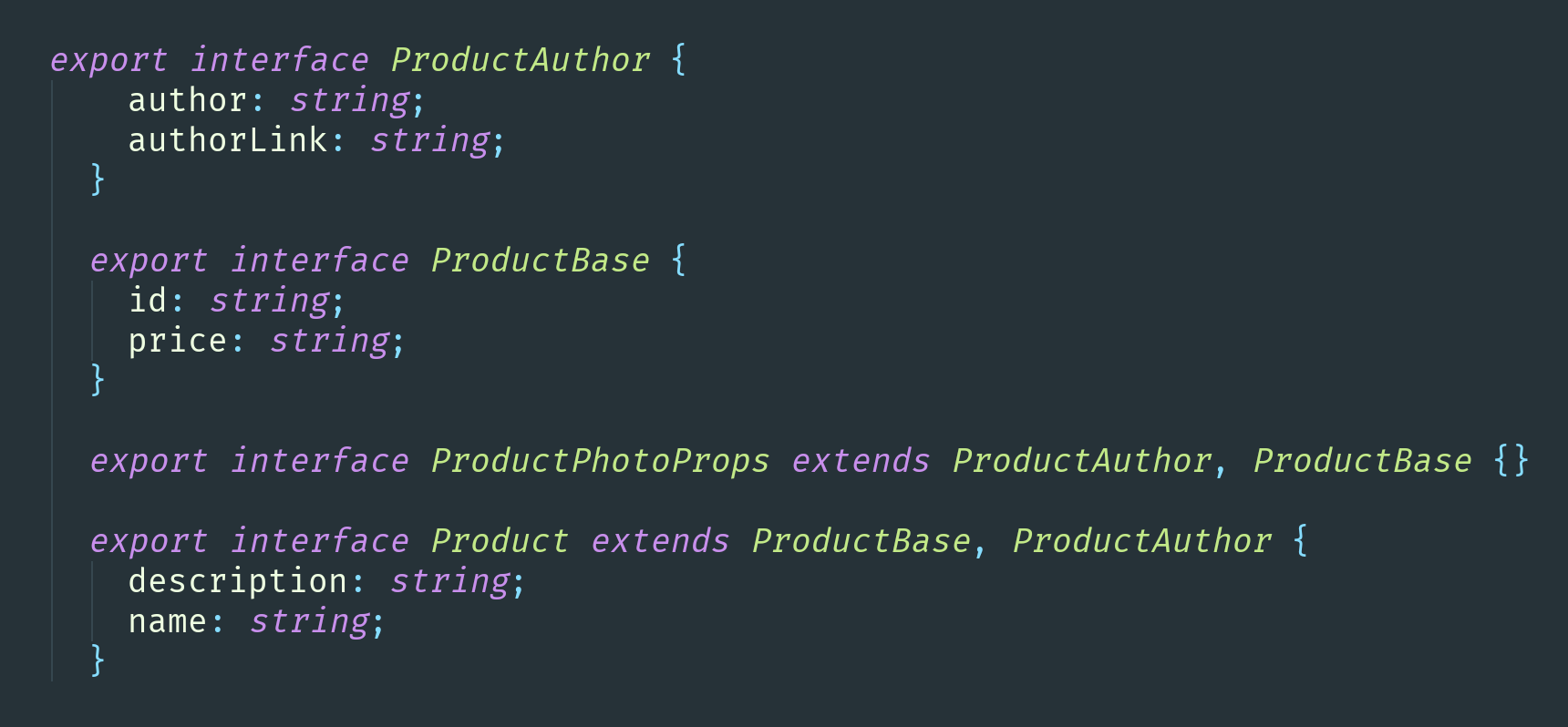

Extending type/interface

When you extend an interface, all properties described in a source interface/type will be available in a result interface. Let’s see how we could combine small interfaces into one that corresponds to our task:

Extending compact interfaces to reuse them for a different component typings

Extending compact interfaces to reuse them for a different component typings

This method is not as handy because you have to imagine the shape of your objects in advance. On the other hand, it is fast and easy which makes it cool for prototyping or building simple UI like rendering data into read-only blocks.

Summary

However, I would like to say one more thing about static typing. Often, when you explore a new technology or face a challenge during a feature development, you start to solve a technical problem and may forget about your goal. Static typing is not a goal of your work, it’s just a tool. If it becomes a central thing of a project, it’s a sign that you got carried away 🚀. Remember about balance in business/tech parts of your app and happy coding!